Zambia Safari: God's Creatures Great and Small

Ecosystem. What is an ecosystem? The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language offers the following definition:

“An ecological community together with its environment, functioning as a unit.”

The introductory photo for this post, a Yellow-billed Oxpecker sitting atop a hippopotamus, exemplifies how disparate species can be adapted for life together. Oxpeckers eat ticks, lice, and other parasites that live on the hides of large mammals (giraffe, zebra, antelope, hippo). Through their vocalizations, these birds may also provide an early warning system of danger to their hosts whose eyesight may not be the best. While I’ve occasionally observed California Scrub Jays picking insects off the heads of browsing deer, the oxpeckers really brought home the concept of symbiotic relationships.

Seeing an ecosystem at work was an enlightening part of my safari experience in Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park. From the trees, bushes, and grasses that provide cover for prey and predator alike, as well as food for a variety of species foraging at different heights, to animals, their remains, and insects whose livelihood support each other, I witnessed so many interactions it is difficult to harness it all in a short article. I’ll give it a whirl, though.

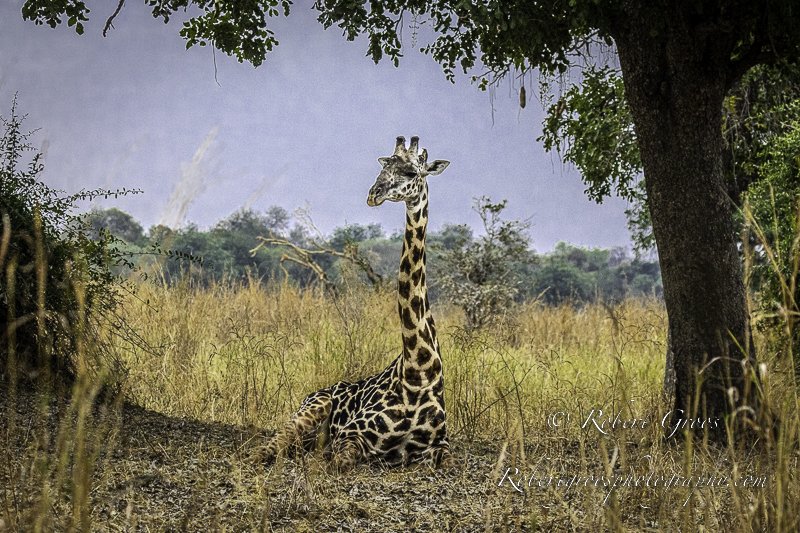

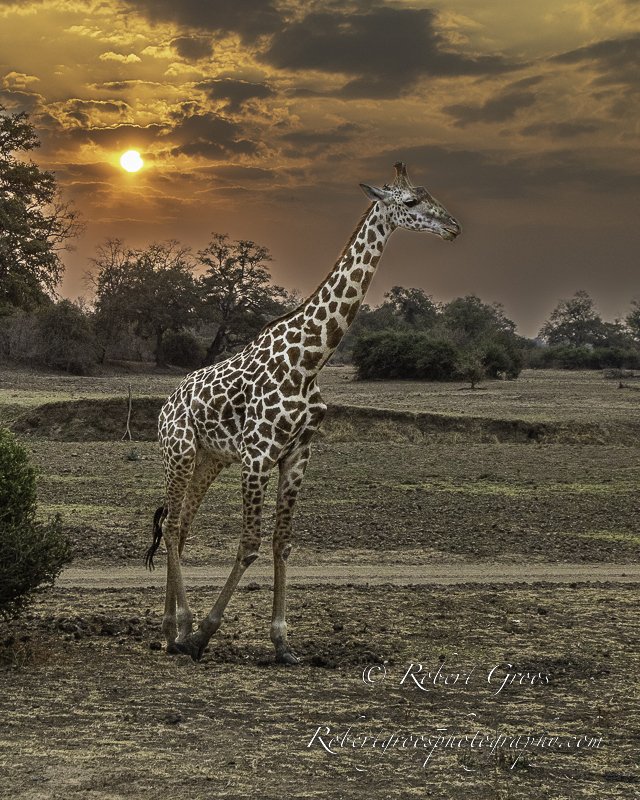

As a photographer attempting to obtain clear shots of my subjects, I could not help to notice how well many animals, with their various colors and field marks, blend in to the surrounding habitat. While foliage provides cover for some prey, it can equally provide camouflage for the predator. No surprise here, but seeing it first hand left an impression.

Southern Carmine Bee-eaters, shown in the gallery below, were a big hit for me. While they do not migrate thousands of miles like some species, they do exhibit a complex, three phase migration pattern. Flocks arrive in their breeding territories during August-September, then spend December-March south of their breeding area, only to depart again in April for territory north of their breeding area. I planned my trip to Zambia during September in order to witness their dense colony nesting in the cliff banks of the Luangwa River, and they did not disappoint. With their carmine-pink-teal-blue colors they are among the most beautiful birds to see. And there were hundreds of them flocking near where I stood.

Southern Carmine Bee-eaters in flight

The video below shows the bee-eaters burrowing into the cliff where they establish their nests. Imagine the sound of hundreds of birds coming and going throughout the day.

Bee-eaters, as their name implies, eat bees, as well as other flying insects. They have a clever adaptation to avoid being stung: by snatching a bee by the wings, then pressing it against a branch to eject the stinger, the bird avoids ingesting poison when swallowing the prey. You can observe that behavior in the video below. A Little Bee-eater is on the left, a White-fronted Bee-eater is on the right.

A Little Bee-eater watches a White-fronted Bee-eater consume a bee.

White-browed Sparrow-Weaver nest

I had previously read about weaver nests, and saw them first hand while in Zambia. Unlike the nests of some ground nesting birds (Killdeer, for example) which are barely a scratch in the dirt or sand, weaver nests are intricately woven, beginning with a single strand of grass. The entrance must be just the right size, not too wide to permit entry by other species; and perhaps having a rear opening just in case of predators. The male weaver does all the work, and may make several nests with hope of attracting a female. Village Weavers construct large colonies of nests in close proximity, hence their descriptive name.

In contrast to the finely constructed weaver nests, the crow-sized Hamerkop bird (so named because of the hammer- like shape of its swept back crest and bill) assembles an expansive, heavy, mud-lined fortress that can weigh over 100 pounds, measure six feet wide and tall, and take three to six weeks to construct. The nest sometimes becomes an attraction for other birds who may nest on top, or even inside. When that happens, the Hamerkop pair may abandon the nest and construct another one or two.

Construction aside, there are naturally occurring sites already in place for birds to occupy. Woodpeckers and chickadees, for example, take advantage of naturally occurring cavities in trees. In terms of predator avoidance, cavity nests may be safer than nests in the open, but not always. The African Harrier Hawk, for example, has double-jointed knees which allow it to probe tree cavities with its talons in search of eggs or nestlings. Thanks to Geoffrey, my astute guide at Flatdogs Camp, I was able to observe such predation in action, as illustrated in the following video.

African Harrier-Hawk hunting for bird eggs and nestlings.

As for the elephant in the room, these pachyderms do just whatever they want to do, whenever they choose. Who is going to tell them otherwise?

During one game drive, an adolescent elephant crossed our path and stopped about 40 feet in front of our jeep. And there it stood, motionless, patiently waiting for rest of his family (which we could not see because of tall brush) to follow. Our guide, turning the motor off, said we could not go around; we had to pause until the matriarch had lumbered by. Considering that a stampede of elephants can ruin your whole day, we waited for fifteen minutes or so for the group to move on. The following video, recorded during a different encounter, demonstrates how a stampede might evolve from a simple walk in the park.

Guess who’s coming to dinner

When not foraging or scratching themselves against a tree trunk, elephants enjoy going to a natural spa for mud bath treatments, which you can watch in this video below.

These elephants do seem to be enjoying themselves, don’t they? I’m thinking beyond the necessity of covering their bodies in mud to protect their skin from insects, abrasions, and other irritants. Just luxuriating in the whole process, like we would do while sitting in a sauna.

I often wonder about animal behavior, and the consciousness they have about what they choose to do. Just consider the baboon in the photo below, with no companions anywhere around, and tell me that it is not contemplating something. It sat there for quite a while, while I was photographing birds not far away. What was it thinking? Was it enjoying some quiet time? Go ahead, anthropomorphize all you want; you’ll receive no criticism from me. Cogito ergo sum, as the saying goes.

A baboon gazes across the river and the savanna beyond.

This post is the third in a series of three about my safari in Zambia, you can find the first story about Big Cats here, and the second, Leopard Sightings, here.

If you enjoyed this post, please share the link with your friends. To be added to my mailing list for future articles, contact me at: robertgroos1@gmail.com. Your information will not be shared, and you can unsubscribe at anytime. Thank you.

P.S. I have so many more photos, but can’t show them all. The gallery below exhibits some of my favorites.

Image Gallery Below:

A pile of Hippos in the Luangwa River

Gray Crown-Cranes foraging